Scott Bessent blamed liberal media coverage for public concerns about cost-of-living, sparking debate over who bears responsibility for economic hardship.

During a Sunday appearance on CBS News’s Face the Nation, Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent offered a striking explanation for why Americans feel squeezed by rising costs. In short, they’re hearing too much about it from the media.

When host Margaret Brennan pressed him on public polling showing widespread concern about affordability and disapproval of the administration’s economic stewardship, Bessent suggested that media coverage itself was shaping voters’ perceptions. “I think the average Americans are hearing a lot of it from media coverage,” he said, implying that the financial struggles Americans report may be more perception than reality.

The comment arrives as the Trump administration grapples with a genuine political challenge. Recent elections and polls consistently show voters deeply dissatisfied with the economy under Republican leadership, with cost-of-living concerns ranking among the top issues driving public sentiment.

The administration has faced mounting pressure to address material concerns about housing, food, and other essentials, yet some officials appear to be taking a different approach: questioning whether the crisis is as real as Americans believe it to be. And we’re always interested in the numbers behind the story.

So while many Americans react with sharp skepticism and frustration, we wanted to evaluate actual inflation data from the past ten years. After all, some commenters have been pointing out the apparent disconnect between official messaging and lived experience.

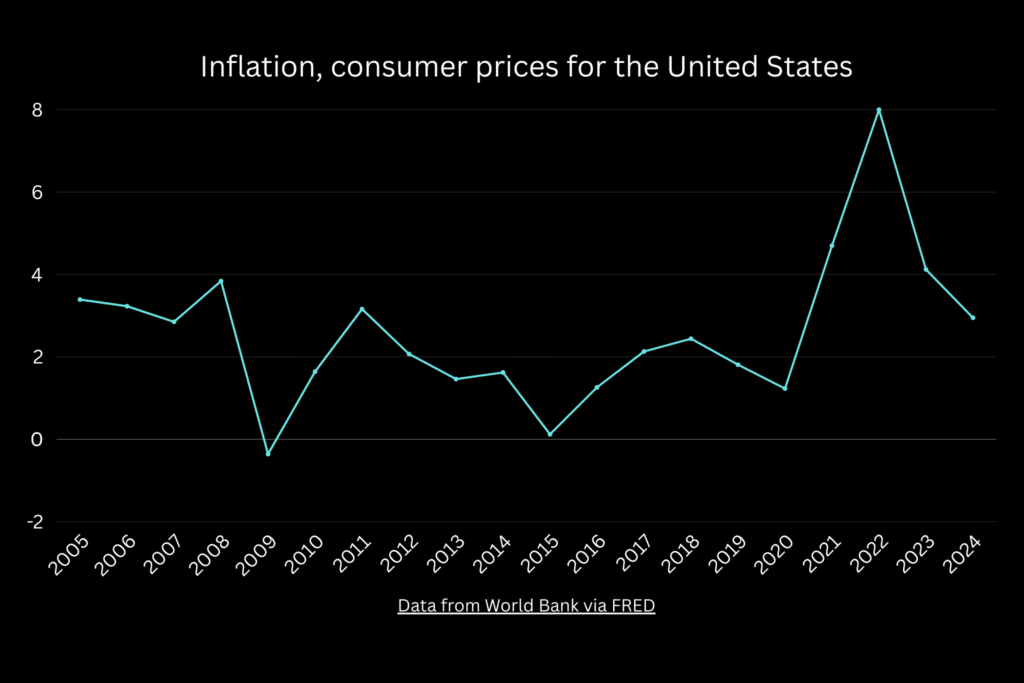

A simple spreadsheet built from the Federal Reserve’s FRED database shows how inflation has actually behaved over the past two decades, including the post-pandemic spike that still shapes how people feel about prices today.

From 2010 through 2019, inflation mostly hovered around the 1 to 2.5 percent range. Those are the kinds of numbers economists describe as “normal” or “stable” for a modern, advanced economy.

In that decade, the outliers were mild: a brief dip close to zero in 2015 and slightly higher readings just above 3 percent in 2011 and 2008. For most households, prices were rising, but slowly enough that many people barely thought about inflation at all.

The picture changes dramatically starting in 2021. Inflation jumps to 4.70 percent, then surges to 8.00 percent in 2022, the highest reading in this series.

Even after that spike, 2023’s 4.12 percent is still roughly double the typical rate of the 2010s. Only in 2024 does inflation ease back under 3 percent, moving closer to its longer-run pattern.

That pattern matters for evaluating Bessent’s claim. If media coverage were the main culprit, you’d expect something closer to a stable inflation series with exaggerated rhetoric layered on top.

Instead, a chart (made from a simple Google Sheets table) shows a real, historic break from the prior decade. The jump between 2020’s 1.23 percent and 2022’s 8.00 percent is a level shift that permanently raised the price of nearly everything people buy.

Even as the rate of inflation cooled in 2023 and 2024, those earlier spikes didn’t reverse. Prices for groceries, rents, and utilities are stacked on top of the 2021–2022 surge, not reset to pre-pandemic levels.

That is why people can look at an official inflation rate under 3 percent and still feel worse off: the monthly increase has slowed, but the baseline they are paying from is much higher than it was five years ago.

For retirees and people on fixed incomes, the picture can be even harsher. Medical costs, prescription drugs, and insurance premiums often grow faster than headline inflation. When you look at the projected Medicare Part B premium increases for 2026 alongside this inflation table, it becomes plain why older Americans are some of the loudest voices in affordability polls. Their costs rose during the inflation spike and continue to drift higher even as the headline rate cools.

Workers in manufacturing and other blue-collar sectors have lived through a similar mismatch between official narratives and lived experience. The long-running decline in manufacturing jobs during the Trump era illustrates how local economies can weaken even when national aggregates look fine. Pairing job numbers with the inflation series above helps explain why communities that lost secure, middle-income work feel particularly battered by higher prices.

The exchange with Bessent ultimately captures a familiar tension in economic politics: leaders prefer to talk about the rate of change; voters live with the level of prices. In this case, the numbers make it hard to argue that concern about cost-of-living is just a product of too much media coverage.