The history of the papacy is filled with unusual, often dramatic events. From a pope put on trial after death to a resignation that broke a 600-year tradition, the Vatican’s past is anything but predictable. But beyond the individual stories, data reveals fascinating trends that help explain how the role of the pope has evolved over centuries.

At first glance, the papacy might seem like a stable institution, with each leader serving a long tenure before passing away. However, a closer look at the numbers tells a different story. Some popes have ruled for decades, while others barely had time to settle into their position.

The Numbers Behind the Papacy

The shortest reign in history belongs to Pope John Paul I, who served for just 33 days in 1978 before his sudden passing. Official reports attributed his death to a heart attack, though conspiracy theories have swirled around the circumstances ever since. At the other end of the spectrum, Pope Pius IX held the papacy for a staggering 31 years, making him the longest-serving pope in history.

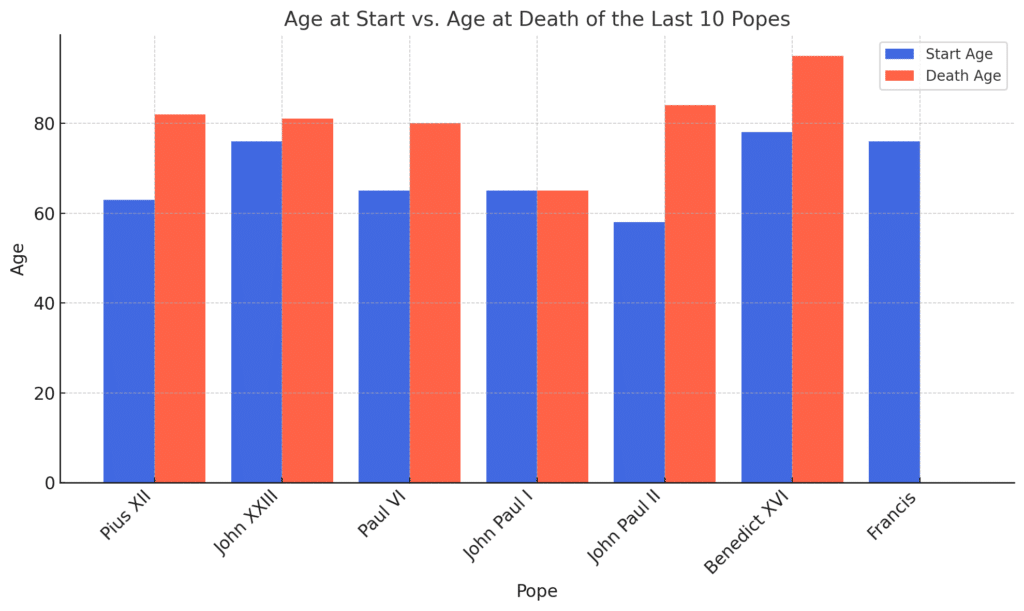

Data also sheds light on how the age of newly elected popes has changed over time. While modern popes are typically in their late 60s or 70s upon election, this was not always the case. The youngest pope in history, Pope Benedict IX, ascended to the position at just 20 years old in the 11th century.

In contrast, Pope Benedict XVI was one of the oldest, living to 95 years old before passing away in 2022. Advances in medicine have likely played a role in extending the lifespans of more recent popes, allowing them to serve longer or live well beyond their tenure.

Although popes now tend to be elected later in life, many still serve for decades. Pope John Paul II, for example, was elected at 58 and remained in office for 26 years, passing away at age 84. His successor, Pope Benedict XVI, was elected at 78 but made history when he chose to resign—a rarity in the papacy.

Resignations are almost unheard of in the Vatican. When Benedict XVI stepped down in 2013, citing health concerns, it was the first voluntary resignation in 600 years. The last pope to do so was Pope Gregory XII in 1415. The sheer gap between these events underscores how rare it is for a pope to leave the position by choice rather than death.

Pope Francis, noted for his austere living choices (choosing to live in a suite at the Vatican guest house instead of the usual palace) is now in his late 80s. And recently, he has faced speculation about whether he might follow in Benedict XVI’s footsteps. However, resignations remain an exception rather than a norm, reinforcing the idea that once elected, a pope typically serves until death.

Medieval Drama and Unusual Events

Beyond statistical trends, some events in papal history read more like medieval thrillers than religious leadership transitions. One of the most infamous moments occurred in 897 AD with the Cadaver Synod, a trial in which a deceased pope was put on trial.

Pope Formosus had already been dead for two months when his successor ordered his body exhumed, dressed in papal robes, and placed in a courtroom. The lifeless pope was found guilty of perjury and other charges, and his body was thrown into the Tiber River. While such grotesque proceedings are no longer a concern, the event remains a stark reminder that political rivalries have long shaped the Vatican’s history.

Another unusual event involved Pope Pius XII, who in 1939 underwent a triple coronation, a practice meant to symbolize the pope’s authority over the church. However, the tradition ended in 1963, when Pope Paul VI discontinued it. Today, popes are inaugurated in simpler ceremonies, reflecting a shift away from monarchical symbolism.

How Data Shapes the Story

The numbers behind the papacy tell more than just who served the longest or who was elected at what age. They reveal deeper patterns—about longevity, the evolution of leadership expectations, and the extraordinary events that have shaped the role of the pope. A data scientist looking at the history of the papacy could focus on trends in lifespans and election ages, while a historian might emphasize the political turmoil and dramatic moments that define its past.

This illustrates a broader truth: data doesn’t tell just one story. It can be framed in countless ways depending on what the storyteller chooses to emphasize. The same set of facts can lead to different narratives—whether one focuses on the endurance of papal leadership, the rarity of resignations, or the bizarre episodes of history.

There are several tools available for collecting and analyzing historical data (like that of the papacy), ranging from simple spreadsheets to advanced programming languages. Google Sheets and Excel are both accessible options for organizing and visualizing trends.

These tools allow for sorting, filtering, and creating charts to highlight patterns such as the average age of election or the frequency of resignations. Excel’s built-in statistical functions, such as regression analysis, can help detect correlations, including whether popes are living longer in recent centuries.

For more in-depth analysis, Python is an excellent choice, particularly with libraries like Pandas for data manipulation, Matplotlib and Seaborn for visualization, and Scikit-learn for more advanced statistical modeling. A data scientist could use Python to analyze longevity trends, compare papal election ages across centuries, or even model hypothetical scenarios like predicting the likelihood of future resignations based on historical patterns.

Diving deeper into the numbers could uncover even more unexpected trends in papal history. One intriguing angle would be to analyze how geopolitical events influence papal elections. For example, were popes elected during times of war or instability older and more experienced, compared to those elected in peaceful periods? Data could reveal whether there was a strategic shift in the types of leaders chosen based on the challenges facing the Catholic Church at the time.

If you want to analyze this kind of data yourself, learn Excel. Or pull the data from a reliable source, clean it, and visualize it. Ultimately, history is not just about events. It’s about the patterns hidden within them. With the right data and analytical tools, the papacy provides a deep well of stories waiting to be uncovered.

For more interesting data insights, visit Spreadsheet Point.